The Tokyo metropolitan government intends to use a new subway line to spur the redevelopment of the city’s waterfront area following the Tokyo Games, and to enhance Tokyo’s competitiveness as an international CBD city.

However, the metropolitan government’s huge investment in this project has raised concerns over its profitability.

“The waterfront area will evolve in the future,” Tokyo Gov. Yuriko Koike said at a press conference Friday. “It [the new subway line] is expected to play an important role as transportation infrastructure, a backbone so to speak, connecting the area with the center of Tokyo.”

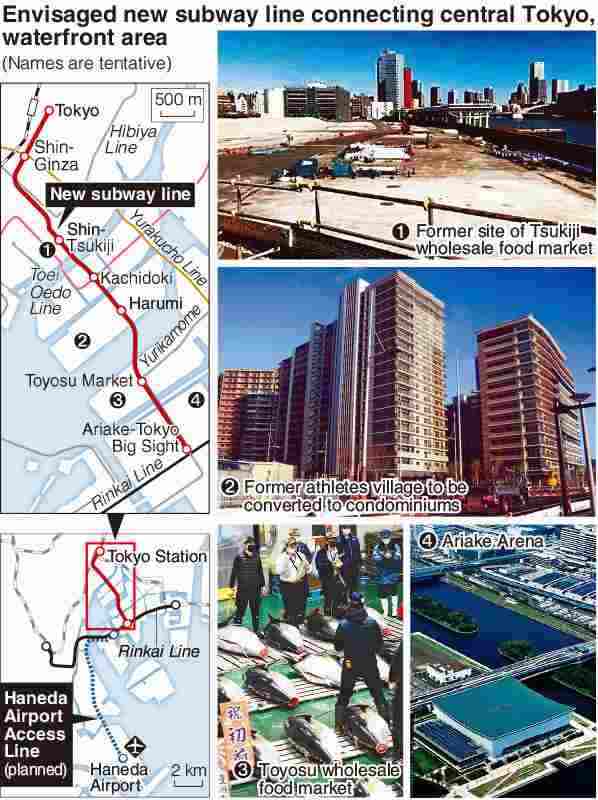

The new subway line is scheduled to be about 6.1 kilometers long with seven stations tentatively named Tokyo, Shin-Ginza, Shin-Tsukiji, Kachidoki, Harumi, Toyosu Market and Ariake-Tokyo Big Sight. It is expected to go into operation around 2040.

Efforts are being made to link the new line to the planned Tokyo Domestic Airport Access Line, which will be operated by East Japan Railway Co. (JR East), and the Tsukuba Express, which connects the Ibaraki and Chiba areas to Tokyo’s Akihabara district.

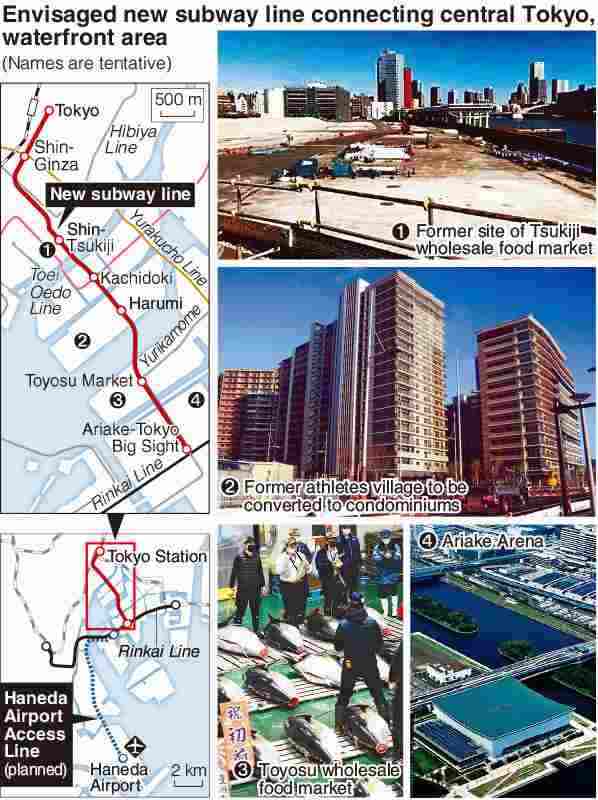

The landscape of the waterfront area, once notable for its vacant lots, has been transformed by the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics. Sports facilities have been built one after another, and new high-rise office buildings and tower condominiums have also filled the area.

The former athletes village in the Harumi district will be turned into a huge condominium area, home to about 12,000 people. A redevelopment plan is also underway for the former site of the Tsukiji wholesale food market, so the population of the waterfront area is expected to keep growing.

The Tokyo Games spurred the development of the waterfront area, and the metropolitan government intends to take this even further. In March this year, the Tokyo government formulated the “Tokyo Bay eSG Urban Development Strategy,” which calls for establishing development bases for cutting-edge technologies, such as flying cars and ships powered by fuel cells. It also seeks the construction of facilities for international conferences and exhibitions, to attract human resources and investment from both Japan and abroad.

However, the waterfront area lacks sufficient railway, bus and other public transportation systems connecting the area with central Tokyo, often causing congestion. The waterfront subway line has therefore been planned as essential transportation infrastructure for the area’s development.

The metropolitan government has been urged on by its strong concern over Japan’s declining international competitiveness.

In 2000, Japan’s nominal gross domestic product per capita was the world’s second largest after Luxembourg, but it ranked 27th last year. In the World Competitiveness Ranking compiled by the Switzerland-based International Institute for Management Development, Japan held the top position until the early 1990s, but has not been able to halt its decline since the bursting of the bubble economy.

This year, Japan placed 34th, falling behind not only major industrialized countries but also China (17th) and South Korea (27th).

Given the situation, the metropolitan government this year launched a loan intermediary program for foreign entrepreneurs to attract overseas investment, and worked out a new strategy to support startups through measures such as establishing a hub where domestic and foreign venture capitalists and research institutions can work together.

“Once the novel coronavirus pandemic is brought under control, international business competition will intensify,” a senior metropolitan government official said. “Tokyo, the capital of the nation, must lead the Japanese economy.”

The cost of the new subway line is estimated at ¥420 billion to ¥510 billion, equivalent to about 10% of Tokyo’s annual tax revenues.

Operated by the metropolitan government, the Toei Subway system has four lines — Asakusa, Mita, Shinjuku and Oedo — and required huge construction costs and incurred operational losses for a long period of time. Development along its subway lines helped increase the number of passengers, and the subway system went into the black from fiscal 2006.

However, it suffered a loss of ¥14.5 billion in fiscal 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic. Its accumulated deficit and long-term debt have amounted to about ¥820 billion.

The Tokyo metropolitan government is aiming to eliminate the new subway line’s accumulated deficit within 30 years after its opening. However, the number of people using the metropolitan subway system has continued to decline by about 30% from the pre-pandemic level.

Due to factors such as teleworking, which has taken root in society, there are currently no prospects for a recovery in demand, making it unclear whether the subway system can return to profitability as projected.

“It’s significant to build a rail line in the waterfront area, where development is progressing,” said Koki Ozawa, a senior analyst of SBI Securities Co. who is well-versed in the transportation industry. However, he added: “Demand from commuting may hit a ceiling. To stabilize revenue and expenditures, it’s necessary to promote urban development that attracts tourists and business travelers from Japan and abroad.”